Let’s journey to the city of London, England, in the summer of 1858. Horse-drawn carriages clip-clop through the streets. Ladies wearing giant, tentlike skirts glide past shop windows. Kids stand on street corners, selling newspapers and cigars and fried fish.

But you don’t notice any of that. All you can think about is the overpowering, stomach-turning, eye-watering smell of poop.

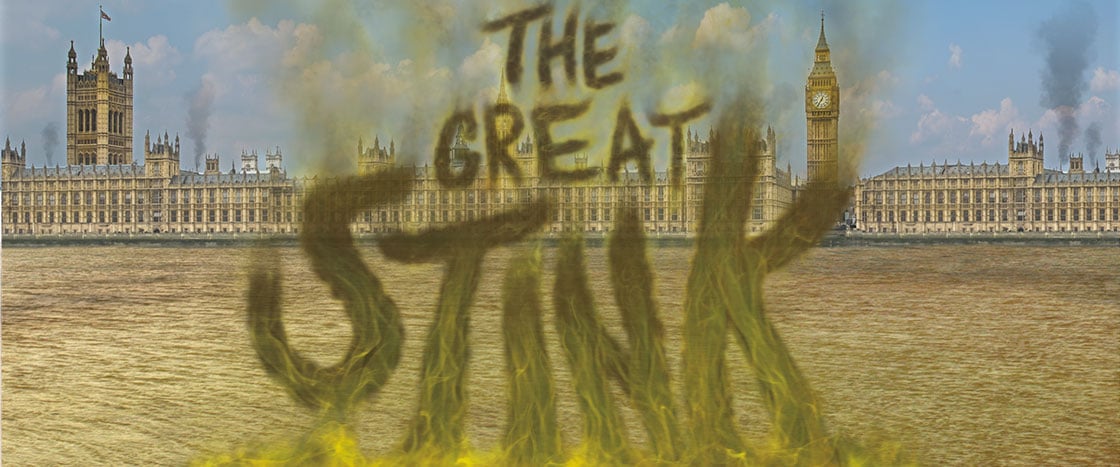

As you will soon discover, the entire city is caught in the grip of a stinky crisis. For years, Londoners have been dumping human waste into the Thames [TEMZ], the great river that rushes through the city. Now, London is suffering the hottest summer in recent history. The steaming heat is cooking the filthy river into a bubbling, foul-smelling stew. Newspapers are calling this crisis “the Great Stink.”

The problem isn’t merely gross. It’s also deadly. Over the past 50 years, tens of thousands of people have died from drinking the polluted water of the River Thames. Can the Great Stink force the city to clean up the Thames before thousands more are sickened?

Let’s journey to the city of London, England. It’s the summer of 1858. Horse-drawn carriages clip-clop through the streets. Ladies in tent-like skirts glide past shop windows. Kids sell newspapers, cigars, and fried fish on the street.

But you don’t notice any of that. All you can think about is the smell. The overpowering, stomach-turning, eye-watering smell of poop.

The entire city is caught in the grip of a stinky crisis. For years, Londoners have been dumping human waste into the Thames [temz] River, which runs through the city. Now, London is suffering the hottest summer in recent history. The steaming heat is cooking the filthy river into a bubbling, foul-smelling stew. Newspapers call this “The Great Stink.”

The problem isn’t merely gross. It’s also deadly. Over the past 50 years, tens of thousands of people have died from drinking the Thames River’s polluted water. Can the Great Stink force the city to clean it up before thousands more are sickened?