Shutterstock.com

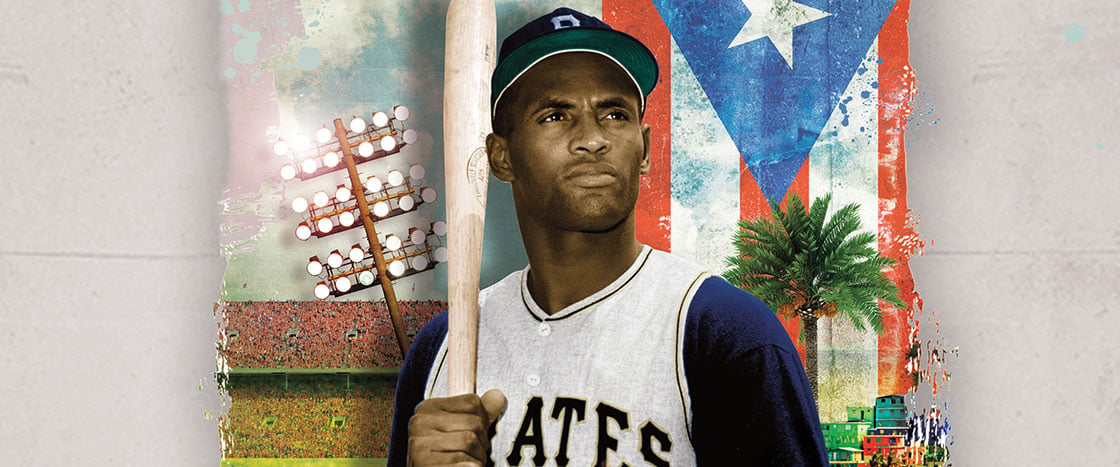

It was the final game of the 1971 World Series, the biggest baseball championship in the United States. The score was 0-0 as the announcer boomed, “Number 21 . . . Roberto Clemente!”

Clemente, the right fielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates, stepped up to the plate. His team was expected to lose to the Baltimore Orioles. But Clemente had promised his teammates they would win.

He had beaten tough odds before. Clemente was a Black Latino baseball player from Puerto Rico, an island that’s part of the U.S. He faced discrimination throughout his career. His incredible talent was often overlooked. But Clemente was always proud of who he was and where he came from. Now he wanted to show the world that he was one of the best players.

Clemente raised his wooden bat over his shoulder and waited. The crowd held its breath. Then the pitcher wound up, and the ball whizzed through the air.

It was the final game of the 1971 World Series. That’s the biggest baseball championship in the United States. The score was 0-0. The announcer boomed, “Number 21 . . . Roberto Clemente!”

Clemente stepped up to the plate. His team, the Pittsburgh Pirates, was expected to lose to the Baltimore Orioles. But Clemente had promised his teammates they would win.

He had beaten tough odds before. Clemente was a Black Latino baseball player from Puerto Rico. He faced discrimination throughout his career. His great talent was often overlooked. But Clemente was always proud of who he was and where he came from. Now he wanted to show the world that he was one of the best players.

Clemente raised his wooden bat over his shoulder and waited. The crowd held its breath. Then the pitcher wound up, and the ball whizzed through the air.