Let’s take a trip back to the 1950s. It’s a time before texting and TikTok, before video games and Netflix. The television is a recent invention, and many families don’t own one.

So what, you may wonder, do kids do ?

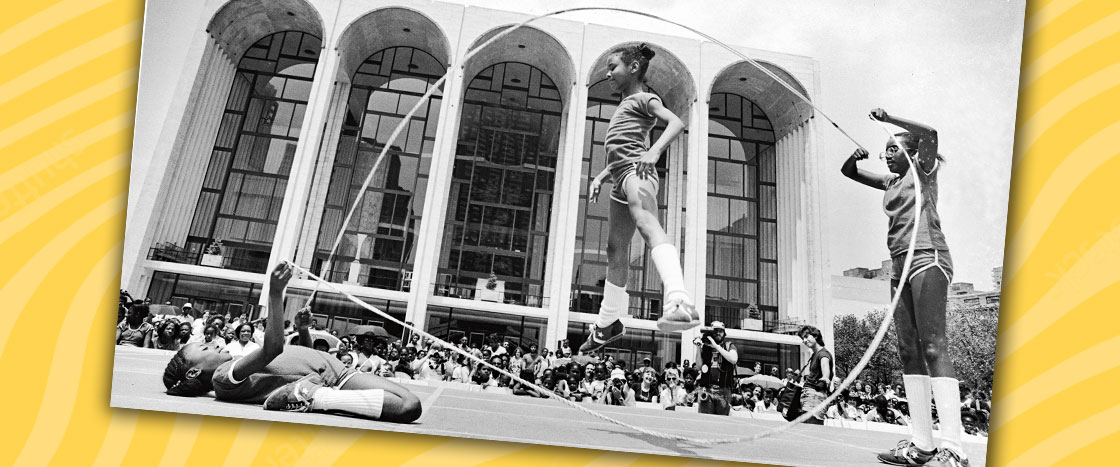

To find the answer, step outside. Walking through the streets, you’ll pass kids thwacking a handball against a wall, shrieking joyfully in the spray of a fire hydrant, and shooting marbles on the sidewalk. And soon you’ll hear it: TICK-tat, TICK-tat, TICK-tat.

That is the sound of two jump ropes flicking against the pavement. Two kids hold the ends of the ropes, turning them in giant circles. But it’s the girl in the middle who draws your attention. She is skipping over the twirling ropes so quickly that her feet are a blur. Other kids chant rhymes to keep her on the beat: “Banana, banana, banana split. What did you get in arithmetic?”

This jump rope game is called double Dutch. One day, it will become an international sport. But for now, it’s simply an after-school obsession.

The girl in the middle jumps faster and faster, until—Eeeeeek ! Her foot catches on a rope, and she gets tangled. Everyone whoops and laughs. As the jumper steps aside, all eyes turn to you. Time to decide: Do you dare jump in the ropes?

Let’s take a trip back to the 1950s. It’s a time before texting and TikTok. It’s before video games and Netflix. The television is a new invention. Many families don’t own one.

So what do kids do ?

To find the answer, step outside. Walking through the streets, you’ll pass kids thwacking a handball against a wall. Some are shouting joyfully in the spray of a fire hydrant. Others are shooting marbles on the sidewalk. And soon you’ll hear it: TICK-tat, TICK-tat, TICK-tat.

That’s the sound of two jump ropes hitting the ground. Two kids hold the ends of the ropes and turn them in giant circles. But it’s the girl in the middle you watch. She is skipping over the twirling ropes so quickly that her feet are a blur. Other kids say rhymes to keep her on the beat: “Banana, banana, banana split. What did you get in arithmetic?”

This jump rope game is called double Dutch. One day, it will become a sport played all over the world. But for now, it’s simply an after-school craze.

The girl in the middle jumps faster and faster, until—Eeeeeek ! Her foot catches on a rope, and she gets tangled. Everyone whoops and laughs. As the jumper steps aside, all eyes turn to you. Time to decide: Do you dare jump in the ropes?