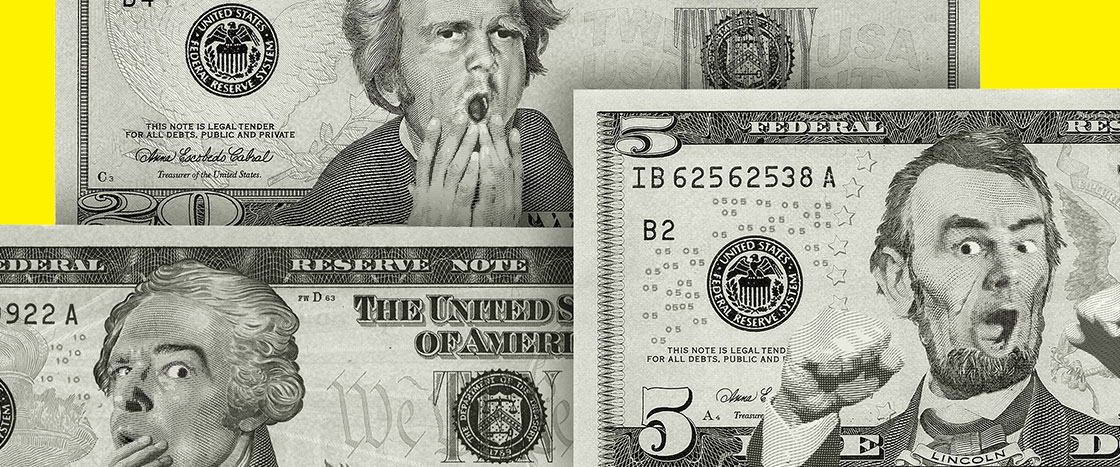

Here’s a riddle: I was invented more than 1,000 years ago. I can be germier than a toilet seat. At least two countries are trying to get rid of me forever.

What am I? Paper money!

For hundreds of years, people have bought stuff with paper money and coins. (That’s also known as cash.) But now we have technology. It’s possible to get almost anything without ever touching a dollar, quarter, or nickel. We can shop online and in stores with credit cards. We can use debit cards. We can use apps on our phones.

“Within 10 years, cash will seem old-fashioned,” says Susan Crawford, a technology expert.

Already, businesses like Amazon, Shake Shack, and Starbucks are trying out going cash-free. Sweden and South Korea are getting rid of bills and coins.

But is there a cost to giving up cash?

Here’s a riddle: I was invented more than 1,000 years ago. I can be germier than a toilet seat. At least two countries are trying to get rid of me forever.

What am I? Paper money!

For hundreds of years, people have bought stuff with paper money and coins. (That’s also known as cash.) But now we have technology. It’s possible to get almost anything without ever touching a dollar, quarter, or nickel. We can shop online and in stores with credit cards. We can use debit cards. We can use apps on our phones.

“Within 10 years, cash will seem old-fashioned,” says Susan Crawford, a technology expert.

Already, businesses like Amazon, Shake Shack, and Starbucks are trying out going cash-free. Sweden and South Korea are getting rid of bills and coins.

But is there a cost to giving up cash?

Mira este acertijo: me inventaron hace más de 1,000 años. Puedo tener más gérmenes que el asiento de un inodoro. Al menos dos países están tratando de deshacerse de mí para siempre.

¿Quién soy? ¡El papel moneda!

Durante cientos de años, la gente ha comprado cosas con papel moneda y monedas. (también conocido como dinero en efectivo). Pero ahora tenemos la tecnología. Es posible obtener casi cualquier cosa sin siquiera tocar un dólar, una moneda de veinticinco o un centavo. Podemos comprar en línea y en tiendas con tarjetas de crédito. Podemos utilizar tarjetas de débito. Podemos usar aplicaciones en nuestros teléfonos.

“Dentro de 10 años, el efectivo parecerá haber pasado de moda”, dice Susan Crawford, experta en tecnología.

Empresas como Amazon, Shake Shack y Starbucks están intentando no usar más el dinero en efectivo. Suecia y Corea del Sur se están deshaciendo de los billetes y las monedas.

Pero, ¿hay algún costo por renunciar al dinero en efectivo?