After a good day at the market, my mother, Yeyo, gave me five whole ten-cent coins. I gaped at the money until Yeyo nudged me. “Saruni, what are you waiting for? Go and buy yourself something.”

I plunged into the market. I saw roasted peanuts, chapati, rice cakes, and sambusa. There were wooden toy trucks, kites, slingshots, and marbles. My heart beat excitedly. I wanted to buy everything, but I clutched my coins tightly in my pocket.

At the edge of the market, I stopped. In a neat sparkling row stood several big new bicycles. One of them was decorated all over with red and blue.

That’s what I would buy!

For some time now, Murete, my father, had been teaching me to ride his big, heavy bicycle. If only I had a bicycle of my own!

A gruff voice startled me. “What are you looking for, little boy?”

I turned and bumped into a tall skinny man, who laughed at my confusion. Embarrassed, I hurried back to Yeyo.

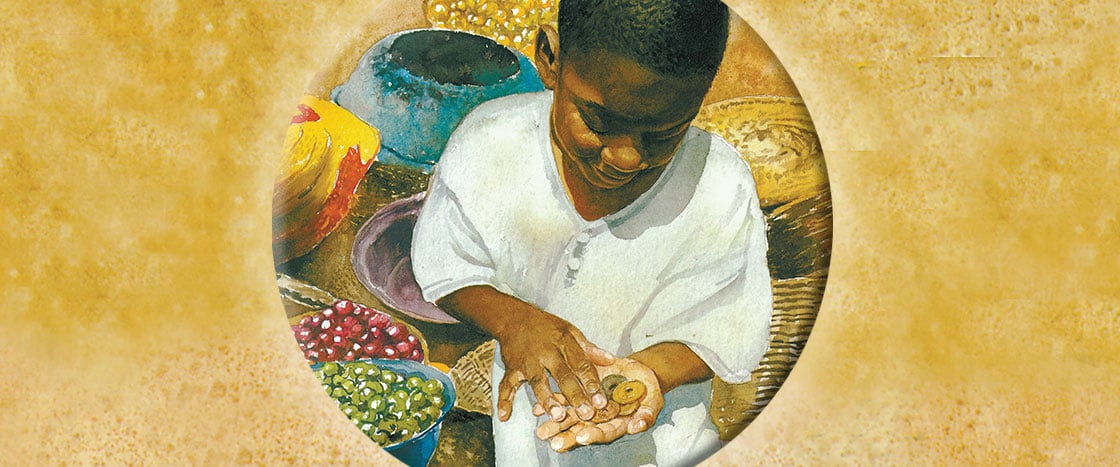

That night, I dropped five ten-cent coins into my secret money box. It held other ten-cent coins Yeyo had given me for helping with market work on Saturdays. By the dim light of a lantern, I feasted my eyes on the money. I couldn’t believe it was all mine.

I emptied the box,

arranged all the coins in piles

and the piles in rows.

Then I counted the coins

and thought about the bicycle

I longed to buy.